Thai waitresses, 'TP' drops and a lightning strike

Thai waitresses, 'TP' drops and a lightning strike

Veteran shares a personal account of the war

June 13, 2010 11:21 PM

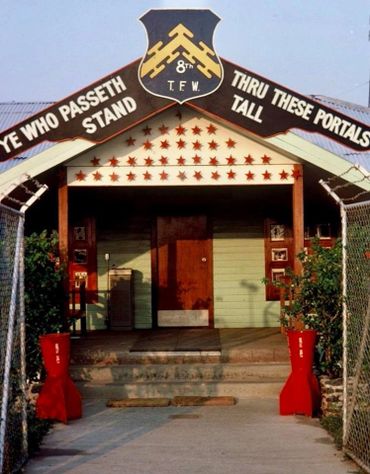

In the summer of 1966, I was single, twenty-five years old, and a first lieutenant flying Air Force F-4s at MacDill AFB, FL. Thanks to President Johnson’s Vietnam buildup, I had recently upgraded to the front seat and, along with the rest of my upgrade class, was on my way to the 8th TFW at Ubon Royal Thai AFB. I would be flying combat missions into North Vietnam.

I spent a few weeks at my home in Oklahoma, said goodbye to my mom and dad at the Oklahoma City airport and headed west. My mom wasn’t too happy. I was an only child and she’d never been big on my going in the military. She’d lost her first child before I was born and was at times, overly protective. My dad didn’t look well. He had suffered a number of heart attacks during the previous five years. My first stop after leaving the states was Clark Air Base, Philippines to spend a week in Jungle Survival School. Next stop was the big one, Ubon. The date was early July and I managed to hitchhike on a C-130 which arrived at Ubon in the middle of the day. Since, the USA was fighting a war and I was going to a unit in the middle of it; I expected a beehive of activity on arrival. Just the opposite occurred.

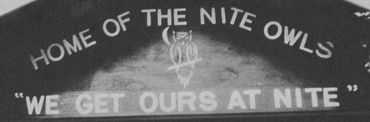

When the 130 shut down and kicked us off, it was so quiet; you could hear a pin drop. No airplanes flying except for an Aussie F-86 air defense detachment. No one was there to greet us. I was pointed in the direction of a long, one story wooden building in the distance, surrounded by a chain link fence. After a half-mile hike with my bags, I finally made it to the DO’s office and found an NCO who told me I was assigned to the 497th TFS Night Owls.

The inactivity continued. I was escorted to the squadron where I finally found the first sergeant. Turned out that the 497th flew at night and everyone was in their quarters resting for their night missions. The sergeant then drove me to the squadron commander’s trailer. There, I found the ops officer outside sunning himself, reading something likeTrue War Stories. The squadron commander met me at the door in his boxers and a Mickey Mouse T-shirt. Such was my introduction to the war zone, the 8th TFW and the 497th TFS.

My ground orientation passed quickly, not much more than a sit down with my flight commander, a map of North Vietnam and a cursory explanation of ground and flight procedures. My first mission was on 7 Jul; but, in the back seat. I had worked hard to move up front; gave up a cushy job to another fighter outfit in England; but, the 497th had a policy that all new guys would fly in the back seat for their first five missions. This was to better orient them in mission conduct and the combat zone itself. An initial disappointment for me; but, the policy saved lives.

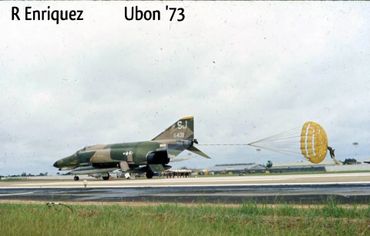

The 497th’s mission was night armed reconnaissance in North Vietnam. We looked for trucks, barges, boats, storage areas, etc. Essentially war materials headed south. Usually missions consisted of two F-4s flying about seven miles in trail. The lead F-4 carried flares on the outboard pylons, weapons on the inboards and a centerline fuel tank. The trailing F-4 carried weapons on the outboard and inboard pylons and a centerline fuel tank. Occasionally, fuel tanks were carried on the outboards and weapons on the other stations. Weapons varied. During my tour, I carried napalm, 500 lb, 750 lb and 1000 lb bombs, rockets, cluster bomb units (CBUs) and flares. Lest I forget, I also dropped a number of leaflets. We called it “toilet paper”.

When I first arrived, the runway was only 7000ft long. By the time I left in Dec, the runway had been extended to 8000ft. I never liked that size runway. By all accounts, that length sufficiently long; but, it looked short to me. As a consequence, we all developed the technique of always deploying the drag chute just before touchdown and touching down in the first 500ft. For takeoffs, we always were careful to position our jets such that we had the entire length of the runway ahead of us before releasing brakes.

Seventh Air Force, from Saigon, South Vietnam, passed the mission requirements to the 8th TFW via “frag” orders and mission assignments just rolled downhill to the squadron schedulers. For control purposes, North Vietnam had been divided into six Route Packs. RP #1 was at the southern end of North Vietnam. At the north end of the country, RP 6 was divided into Alpha and Bravo. Alpha contained Hanoi. Bravo contained Haiphong. During this timeframe, the overall effort was called Rolling Thunder.

My first front seat ride was on Mission #6, 11 Jul, just four days after my first mission. One hundred missions into North Vietnam was our goal. Due to the exceptionally high risk of flying in the highly defended North, 100 missions was considered a complete combat tour and the Air Force sent you back to the states. We flew almost every night; so our mission count built up quickly. The weather had to be really crummy for us not to fly.

We got shot at practically every mission. Most of the defenses were manually fired 37/57mm AAA. At night you saw blue and red tracers. You watched the ground carefully because you wanted to spot the tracers as early as possible in order to maneuver away from the shots. If you saw bright white flashes, you were receiving 85mm AAA fire. As soon as the flash occurred, you’d change the aircraft heading and altitude immediately because those rounds were radar aimed with no tattle tale tracers and the gunners had a radar lock on your aircraft. At the time, Surface-to-Air Missile sites were located primarily in the Hanoi and Haiphong areas, i.e. RP 6A and RP 6B. We flew most of our missions in the other RPs.

Speaking of 85mm rounds; the recce RF-4s would scare the crap out of us at night. They shot flares out the side of their aircraft to illuminate the terrain for their pictures. When these flares first initiated, they looked exactly like 85mm flashes. During the wing’s general briefing before our night’s work, they would always tell us the RFs would be in the area; but, that was all—no times, routes or headings. We could be in the middle of a target run and out of nowhere; we would see these bright flashes headed our direction. For a few seconds; we thought we were toast, and then we realized what was happening and gave the RFs room until they were out of the way. I once actually witnessed an RF-4 fly underneath our flare light. Guts ball.

I reached my 100 mission goal in early December 1966; but, before I address those missions, a bit about life on the ground. All the crews stayed in one story buildings we called “hooch’s”. The hooch’s were built out of Thai teak wood, six rooms to a building and two people to a room. Each building had central bathroom facilities. A local Thai (called a hooch-boy) was assigned to each building. He kept the place clean and got our clothes washed. We slept during the day and flew all night. As a result, we got the room air conditioners. The day guys slept at night and had to depend on cool night air.

Our hooch’s were about two blocks from the officer’s club. Our off duty ground life centered mostly between those two areas. We were literally flying seven days a week during my tour and didn’t have much extra time for off duty activities. Several things I remember about the O’ Club. First, the only females in the vicinity were a few Thais hired to work in the bar or restaurant. They spoke little English. In the restaurant, this problem was resolved by a limited menu with numbers. Each number was a complete meal. You picked out your choice and gave the corresponding number to the waitress. This worked okay for the most part; but, I still remember one guy ordering bacon and eggs. He got a banana and peanut butter. Go figure. We had two waitresses we nicknamed Powder Puff and Two-step. Powder Puff got her name because she was very cute and spoke some English. She also spoke some Vietnamese. Who knows, she might have been a spy. Two-step got her name because two steps away from the table and she forgot what you ordered.

About a month or two after I arrived, the O’ club built a stag bar. Why they did this, I never figured out. The whole club was already a stag bar. The only females present were the Thai girls I previously mentioned. Nothing changed. The same guys and workers frequented the stag bar as frequented the club before. The first night the stag bar was open, we got into a big water fight and tore up the place. The stag bar then closed for a week for repairs. The base chapel was used as a movie theatre at night. The movies were really old. I kept thinking they might be holdovers from WW II.

We had an FM radio station with about 10 watts of power. Our communication back to the states was limited to snail mal.

Despite flying seven days a week, we occasionally made it to downtown Ubon. Transportation was via public transportation. We called it the “one baht” bus. At that time, the Thai baht was worth about a nickel U.S. The seats were sized for the Thais; not us. Consequently, each of us took up about two seats. The Thais found a way to keep a number of people employed. Thai manning for each bus consisted of a driver, a person selling tickets and another person taking them back.

Since the 497th flew all night, we always celebrated another 24 hours of survival with a few drinks at the club bar in the early morning hours. Drink prices were about 25 cents per. We were eating the last meal of our day when the day guys arrived to eat their first meal.

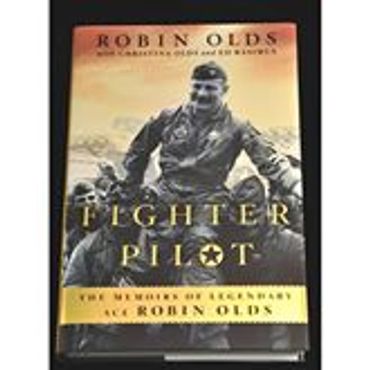

ROBIN OLDS WELCOMED TO UBON

In late August or early September, four or five of us lieutenants were leaving breakfast when in walked this unknown full bird colonel wearing a flight suit with F-101 Wonder patches all over and the verboten knife pocket still sewn on. Since fighter pilots wore g-suits with knife pockets and never used the flight suit knife pocket; an unwritten rule was that pocket had to go. The 8th TFW was an F-4 outfit, not an F-101 outfit plus you were not allowed to wear patches in combat, only a name tag

We lieutenants decided we needed to correct this situation and we attacked. This colonel was a big man and he did not go down easy. The wrestling contest moved outdoors. We finally managed to get all the patches plus the knife pocket and ripped his flight suit in the process. One of our guys got a black eye out of the affair.

Turned out the colonel was Robin Olds and this was his first day in command of the 8th TFW. Olds told his Vice he’d be late for the morning briefing and went back to his trailer to change flight suits. We lieutenants walked back to our hooch’s to go to bed. We never heard another word about the affair.

On page 257 of "Fighter Pilot" Col. Olds relates the incident at Ubon. It appears that perhaps Col Olds was mistaken on the name of one of the lieutenants.

I kept a log of all my missions; primarily because I was warned by the old heads that the wing sometimes misplaced a mission here and there. Better to have your own data to back up when you reached your 100 mission goal. Over the course of a hundred missions, our daily agenda became routine. Sleep all day; hit the club for an early dinner, a mass aircrew intelligence and weather briefing before the night’s activities, individual flight mission briefings, crank the aircraft and go, go again if necessary, to the club for a few drinks, breakfast, off to bed, repeat same eight hours later. A few missions I remember like I flew them yesterday. Those are the ones I’ll address. The common thread among them is that it’s better to be lucky than good.

Mission #?? (some time between #6 and #13): Flying night combat was different than day. The day light guys had learned, the hard way, to stay above 8,000ft or more to avoid ground AAA to the max extent possible. At night, if you really wanted to be effective, you had to get down in the dirt. A lot of guys were hesitant to do this. You seriously exposed yourself to enemy fire plus it was night and you were close to the ground and mountains. We operated in a lot of rugged territory with little room for error.

Crossing into North Vietnam, we turned off all our external lights and armed all the weapons. All that was left was to press the bomb release button (aka “pickle” button) at the appropriate time. On this mission to RP 1, Major Larry Gardner was flying the lead ship with flares. He picked a north-south narrow road running between two ridge lines and flared. We caught about four trucks in the open headed south. I was the one with all the bombs and rolled in, pointed my nose down and started to track the target. Unfortunately, I’d made a fundamental error—I was too shallow.

The pipper on my sight was way beyond the target. I had three choices, abort the run, bunt or roll over and pull the nose down. I wasn’t about to abort. Bunting is pushing the nose down and a cardinal sin in dropping bombs. Beside the negative “g” forcing you and every loose item in the cockpit to the top of the canopy, you are guaranteed to miss. I chose to roll over and pull the nose down to short of the target. Normally, if you first roll left, you should roll back right to wings level to stay oriented. I didn’t. My instantaneous thought was that since I was already upside down, why not continue the roll? I did. I continued the dive to well below the flares and between the ridgelines to drop the bombs. I hit the target. Gardner was ecstatic and said so over the radio. He’d been bitching about all the guys who wouldn’t fly below the flares and mix it up in the dirt. Now he’d found someone who would and he was a happy man. In sum, in a 30 degree dive, at night, with a load of bombs, in the mountains, between two ridge lines, I’d rolled that F-4 360 degrees, illuminated myself under the flares and lived to tell the tale. Do not try this at home.

Mission #13, 18 Jul 66: Probably not many guys have been struck by lightning while flying with a load of bombs and lived to tell the tale. I have. We were short on aircrews for the missions that night; so, I was relegated to the back seat again. We were on our way to RP 1. Our jet was loaded with 750lb bombs with manual fuses (fortunately not electrical). I saw some “weak” thunderstorms on the radar and asked the front seater if he wanted to go around or through. He said “straight through”. In typical bored back seater fashion, I put both arms on the canopy sill and rested my feet on the rudder pedals.

I can still see the lightning bolt flashing from above and striking the F-4’s nose. An electrical charge went through me. I lost all color vision. All I could see were shades of black and white, much like a picture negative. We turned around and headed back to Ubon, declared an emergency and landed. About five minutes after the lighting strike, my vision returned to normal. Turned out the lightning entered somewhere on the radome, blew a radar fuse and exited through the left aft wingtip light. Burned out the light bulb and blackened the red light cover. Didn’t blow-up the bombs. We were lucky.

Three hours later, I was back in the air, again headed to North Vietnam, this time in the front seat. In today’s Air Force, I’d probably have been sent to the hospital for several days to check me out; but, this was 1966 and we were short of aircrews. The law of supply and demand affects everyone including the Air Force. For the rest of my 26 year Air Force flying career, whenever I was close to a potential lightning source, I put the plane on autopilot; put my feet on the floor and my arms on my legs. Stayed as far away as possible from any metal. Never got hit by lightning again.

5 Sep 66: No mission here; but, I had completed two missions earlier that morning, one to RP 6A. I was fast asleep when I heard a knock at the door. A sky cop was at the door and told me I should go see the local Red Cross representative. I immediately knew it was about my dad. Sure enough that’s what it was. He’d suffered one too many heart attacks and passed away. I was cleared for emergency leave and hitchhiked my way home to Oklahoma to help my mom. I spent the first night at Clark AB in the apartment of my friend from pilot training, Lt Gary Boris. Gary was indirectly involved in several of my future RP-6A combat missions. My emergency leave was open ended; but, after a couple of weeks at home, my mom surprisingly insisted I return and complete my tour, which I did.

One thing that concerned me the entire time I was home was what was happening back in the 497th while I was gone. After completing the aforementioned mission to RP 6A, I had volunteered for another one the next night. Because I left on emergency leave, someone had to take my place. While home, I constantly worried whether my replacement had made it to RP 6A and back safely. Fortunately, he had. I would have been beside myself if he hadn’t.

Mission #84, 2 Nov 66: Most of our night missions were two ships; however, for special missions, we occasionally put three ships in the formation. Such was the case on 2 Nov when the squadron was tasked with bombing the Viet Tri rail complex, about 35 miles northwest of Hanoi. The Thuds (F-105s) had hit it during the day and we were to follow up that night while the North Vietnamese were repairing the damage. We were #2 in the flight. Lt Grady Reed, my assigned crew member, was in the back seat. Our jet was loaded with 18x 500lb bombs, which with a full centerline fuel tank maxed out the F-4’s takeoff weight at 58,000lbs. This was an important Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) mission because the wing had loaded two spare aircraft with the same configuration. I know this because Grady and I ground aborted two jets before we got in one that fully worked. By the time we got the third one going, the other two jets had left. A max gross weight takeoff at night is not a lot of fun; but, we did get airborne and hightailed it to the tanker. We were now number three in the flight. The flight lead and new number two left the tanker while we were still refueling. Grady and I were to catch up as best we could.

We didn’t have any of the gee-whiz avionics systems of today’s Air Force; but, eighty-three night missions had taught us a lot of work-a-rounds for combat night flying. Grady was working the radar ground mapping the terrain ahead. The radar altimeter provided an altitude trend to the terrain below and the inertial nav gave us an idea of where we needed to go. But, the best aids were plenty of moonlight, TACAN Channel 97 (Lima Site 85) and a lot of map and photo study before the mission. We descended to just above the mountain tops and picked up Ch 97. We stayed as low as possible and when the mountain tops got lower, we got lower too. It’s amazing how close to the deck you will fly when you are trying to avoid getting killed. By then, I was repeating the 23rd Psalm to myself, multiple times.

Viet Tri was located 108nm from LS 85, at the confluence of the Red and Song Lo Rivers. Our three aircraft maintained about a seven mile trail separation from each other and if things went right, we would individually pop to the north of Viet Tri and roll-in to the south. The best clue you were on course was picking up the Red River, about 7nm west of Viet Tri. You then followed that river while glancing to the right. Shortly, you would see Viet Tri in the moonlight.

About two minutes out, I heard “Lead’s up” and shortly thereafter, “Lead’s in”. Then I saw the tracers at lead’s approximate location. Next, I heard the up, in and off calls from number two. This time, the tracers came quicker and thicker. My thoughts changed to “Oh Sxxx—this is gonna suck!” I took a couple of deep breaths, muttered “Why me God?” and it was our time to go. I delayed the pop a few seconds to come down the chute on a different track than our predecessors. I pulled up as sharply as eighteen bombs and full mil would allow. No tattle-tale burners. Grady was calling altitudes and when the picture looked good, I rolled right and pulled the nose down hard.

I wound up with a 15o—20o dive; put the target at the top of the sight, let the piper track to the target and pushed the pickle button. Simultaneously, all hell broke loose. The tracers came on all sides. No matter where I looked, they had us bracketed. Tracers were above us, below us, to the right and to the left. They were lighting up the cockpit with no end in sight. This was definitely an “Oh Sxxx” maneuver and our fate was sealed. I continued tracking; but, there appeared to be no way out and I waited for the first hit. Then a minor miracle—I saw a gap up and to the right. I jerked the jet through that gap and we escaped. Probably laid on at least six G’s if not more. I dove for the deck and stayed there. The only audible sound over the intercom for the next five or so minutes was heavy breathing and a high heart rate.

We headed back toward Ch 97 and then to a tanker. Finally arrived back home, dropped our gear at the personal equipment room, drank a shot of that rotten mission whiskey, debriefed intelligence, went to the O’club, ate breakfast and went to bed. Two nights later, I would fly virtually the same route, except this time, the objective was Hanoi.

A side note on Lima Site 85. LS 85 was a highly classified operation to establish a Tacan in northeastern Laos, atop a 5000ft mountain, west of Hanoi and close to the North Vietnam border. Aircrews would use it to help guide them to targets in North Vietnam. It was especially helpful to the night flyers. LS 85 was established in the latter half of 1966; but, was run over by North Vietnamese commandos in 1968, killing 11 USAF personnel and ending the effort. The project was not declassified until 1983. A major reason I mention this is that Lt Gary Boris, my friend from pilot training, was responsible for initially setting up the site. Google Lima Site 85 sometime for a very interesting story.

Mission #86, 4 Nov 66: This was the “toilet paper” mission to end all “TP” missions. I led a flight of two to deliver thousands of leaflets over downtown Hanoi during the night. President Johnson had recently attended a meeting in the Philippines with other area leaders to discuss where we were going in the Vietnam struggle. The leaflets reflected several pictures from that event plus messages in Vietnamese.

A “TP” drop over Hanoi had never been done before. It was a precedent setting mission and I was leading it. The route was near identical to the one Grady and I’d flown two nights before. After leaving Ch 97, a few degrees heading change to the right got the job done. The problem was the delivery method recommended by 7th AF HQ: 5,000ft altitude, straight and level and 350 knots airspeed over downtown Hanoi. That was as stupid as they get, a sure ticket to the Hanoi Hilton if you survived the hits from the AAA and SAMs.

Larry Gardner and I found some toss delivery tables. My flight would ingress to Hanoi, on the deck, and at the appropriate time, pull the nose up to a 20° - 30° climb angle and at the proper altitude, pickle off the leaflet carrying devices. The containers looked like 750lb bombs from the outside; but, actually they were two shells, clamped together, with a timer fuse to split them apart at the appropriate time.

The flight proceeded much smoother than the one to Viet Tri. After the tanker, we passed over Ch 97, picked up the appropriate radial and got down on the deck. The moon was out with few clouds around. I used the radar altimeter to help with the altitude. When we were over a river or lake, I kept the altitude between 50ft and 100ft. When crossing over any mountains, I mentally projected our flight path and aimed the jet over the lowest dip in the horizon. Once out of the mountain ranges, we stayed down on the deck all the time. If you check a map, you’ll find a portion of the Red River points directly at Hanoi from Ch 97. We stayed over that segment as long as possible. After that, finding Hanoi was easy. It was lit up like a Christmas tree.

I pushed the power to full Mil and at the edge of the Hanoi lights, I pulled the nose up to the chosen climb angle. At the preplanned altitude, I pickled off all the leaflet containers, rolled upside down, pulled the nose back to level flight, then executed a hard left diving turn and quickly got back on the deck. Then back to Ubon the same as two nights before.

I think we sneaked in pretty well. Didn’t receive any AAA until after we were on the way home and that wasn’t much. The toss delivery was one hell of a lot better than that thought up by someone from 7th AF or higher. That leaflet delivery made the Bangkok Times the next day as well as a number of U.S. papers. I still have two of the leaflets. Power Puff translated them for me and I kept the translation.

One thing that puzzled me was that when I rolled over to pull the nose down, I saw some lights that looked very familiar. I’d never been to Hanoi and was trying to figure out what I’d seen. I finally concluded they were the approach lights to Hanoi’s Gia Lam airport. Airfield approach lights are similar all over the world and Hanoi’s were no different. Some years later, when I learned that President Johnson and his cronies planned missions in the RP 6 areas over lunch in the White House (permission to conduct missions in those areas had to come from the highest levels); I often wondered if the planning for that mission was developed there. Was I to be a sacrificial lamb if necessary? Pure speculation on my part; but, I’ll always wonder.

Mission #100, 3 Dec 66: My last mission was a Skyspot to RP 3 with 6x 500lb bombs on each aircraft. This method of bomb delivery was used when the weather was too bad to work close to the ground.

The monsoon season hit North Vietnam toward the end of November which forced us to either use the Skyspot method of bomb delivery or stay home. Seventh Air Force elected to keep us busy.

Skyspots sounded good on paper; but, didn’t work that well in practice plus, from an aircrew perspective, you were a perfect set up for a surface-to-air missile shot. A flight of two or three jets, loaded with bombs, would fly a relatively close finger-tip formation, probably at 10,000ft or higher, and under the control of a radar site. The controller would provide vectors and a countdown. Everyone would hit their pickle button on the controller’s call. Not much to write about except it was the last mission and I would soon be on my way home.

Windup: Remember the ado with Robin Olds? Well several days after my last mission, I was waiting for orders and the weather had turned chilly. I wore a flight jacket to the club. The jacket was still adorned with patches from my previous assignment because the weather had always been too warm. Olds saw me and told me not to ever come back to the club with that jacket on. I guess he had the last laugh.

My next assignment was Instructor Pilot in the 434th TFS at George AFB, CA; again as a first lieutenant. Bought myself a brand new Corvette to celebrate making it back alive. Applied for Test Pilot School at the behest of Larry Gardner and eventually made it.

Cheers,

Jim Sharp

THE BEST OF THE BEST

Who was Robin Olds?

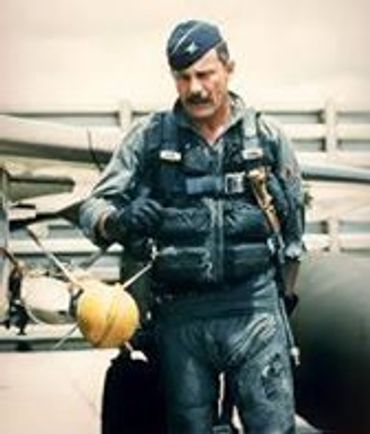

Photo Gallery 497th Night Owels